New World Order?

March Madness took on a whole new meaning for me last month. Rather than logging endless hours watching basketball, studying tournament brackets, and, of course, lamenting the fact that my Demon Deacons didn’t get invited to the Big Dance, I spent most of my time trying to figure out the true objectives of the Trump administration with regard to tariffs and trade policy. Count me among those investors who assumed that Trump’s tough talk about tariffs and trade sanctions was just that—tough talk. Up until mid-February, when the stock market hit an all-time high, it was clear that most investors assumed the same.

That changed today, “Liberation Day,” so designated by President Trump when speaking to reporters in the Rose Garden this afternoon. He stated, “April 2, 2025, will forever be remembered as the day American industry was reborn, the day America’s destiny was reclaimed, and the day that we began to make America wealthy again.” He also called it “one of the most important days in American history,” emphasizing its significance as a “declaration of economic independence.” Trump argued that his reciprocal tariff plan—imposing a 10% baseline tariff on all imports and higher rates like 34% on China and 20% on the EU—would reverse decades of unfair trade practices, generate “trillions and trillions of dollars” to cut taxes and reduce national debt, and usher in a “Golden Age of America” by boosting domestic production and jobs. We expect global stock markets to have a very unfavorable reaction to this new plan.

As we enter the second quarter of 2025, it is now clear that the Trump administration is committed to an economic framework that signals a significant shift in how the United States positions itself globally. This vision, a “New World Order” in economic terms, centers on reshaping trade policies and revitalizing American manufacturing. It’s an overwhelmingly ambitious plan that would redefine decades of global trade norms and bolster domestic industry. In this letter, I’ll dig into the thinking of the people on Trump’s team, discuss our trade policy in an historical context, explain why Trump’s plan is such a dramatic departure from the status quo on trade, outline the economic risks of the plan, and finally, discuss implications for investors.

The Core Vision

The administration’s approach, laid out in the “America First Trade Policy” memorandum signed by President Trump on January 20, 2025, calls for a comprehensive review of US trade relationships and industrial capabilities. This isn’t a minor tweak—it’s a reimagining of America’s role in the global marketplace. The goals are straightforward: cut reliance on foreign supply chains, boost national security through economic self-sufficiency, and put American workers and businesses first. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has pushed this hard, saying, “We’re tearing up the old playbook—trade has to work for America first, not the other way around.” Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick calls it a historic pivot: “This is our chance to reset the global board and bring back what we’ve lost; it’s not just policy, it’s a new era.” It’s a break from the free-trade consensus of the last 80 years, and leans on tariffs and incentives to bring economic activity home.

At its core, this plan tackles trade imbalances, the loss of manufacturing jobs, and vulnerabilities like those exposed by COVID-19. It’s a reaction to decades of offshoring and a bet that the US can reclaim its industrial edge. The scope is huge, covering trade deals, tariffs, taxes, and massive industrial investment.

Trade Policy: The Engine of Change

Trade policy drives this agenda. On February 1, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order slapping tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico, and China—25% on most products, with a 10% rate on Canadian energy to ease price shocks. Using the justification of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the Trump administration aims to pressure partners on issues like immigration and drug trafficking while nudging production stateside. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced NAFTA, appears to be in jeopardy as these tariffs challenge its framework ahead of a 2026 review—a big shift in our historical alliances with Canada and Mexico, our two largest trading partners.

The 2025 Trade Policy Agenda, delivered to Congress on March 2, pushed for a “rebalancing” of trade, targeting deficits and practices like foreign subsidies and value-added taxes. It proposed a universal 10–20% tariff on all imports, with a 60% rate being considered for China. It included threats of 100% tariffs on BRICS nations who are considering adopting alternative currencies to the dollar, showing that trade can double as a geopolitical weapon. It announced that steel and aluminum tariffs from Trump’s first term were under review, while export controls were being tightened to guard America’s technology lead and intellectual property, especially from China.

Finally, and perhaps fittingly, I’m writing this letter on April 2, deemed “Liberation Day” for US trade policy by Trump. Today the president announced a 10% across-the-board tariff on all imports and additional tariffs on any country with whom we have a goods trade deficit (we import more goods from them than they import from us). The larger the deficit as a percentage of the amount that country exports to us, the larger the tariff. For example, with China, the US had a trade deficit of approximately $295 billion in 2024 (their exports to us exceeded our exports to them by $295 billion), and their total exports to us were $440 billion. Dividing $295 billion by $440 billion yields roughly 67%, which when halved, rounds to the 34% tariff Trump plans to charge. The net effect of this approach is to punish any trading partner where an imbalance exists. If we buy more from you than you buy from us, we are going to hit you with a tariff. This approach obviously ignores consumer preferences and distorts the free market. Trump’s team says it doesn’t matter, and that the tariffs will immediately create a powerful incentive for our trading partners to buy more from us.

Bringing Manufacturing Back: A Herculean Task

The vision of the Trump administration is that the US would return to being a “manufacturing powerhouse” with tariffs making foreign goods pricier and encouraging US production. The plan calls for cutting regulations, streamlining permitting processes, and providing tax incentives to encourage businesses to invest in US-based manufacturing facilities. Companies, domestic and foreign, are being incentivized to create American jobs and to build manufacturing plants within the United States. Biden-era moves like the CHIPS Act are building blocks, now refocused with an “America First” lens. Finally, recognizing the existence of a significant skills gap, the administration emphasizes the expansion of vocational training and apprenticeship programs through partnerships with community colleges and trade schools.

A Major Departure

The Trump administration’s plan to remake America as a manufacturing powerhouse represents a major shift in US economic strategy, modifying a decades-long commitment to free trade that began with the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. Anticipating the end of World War II, representatives from 44 nations gathered in New Hampshire and signed a compact establishing a global monetary framework—fixed exchange rates, the IMF, and World Bank—to foster open markets and economic stability, laying the groundwork for a global economy. Globalism, the idea that nations prosper through interconnected trade and investment, took root alongside the principle of comparative advantage, which most economists, from David Ricardo in 1817 to modern thinkers, have embraced. This holds that countries should specialize in what they produce most efficiently— making car parts in Mexico, assembling tech in China, or designing microchips in the U.S for example—and trade freely, maximizing global wealth. It’s why your iPhone’s components crisscross the globe before landing in your hand. Your phone would cost far more if built in the US.

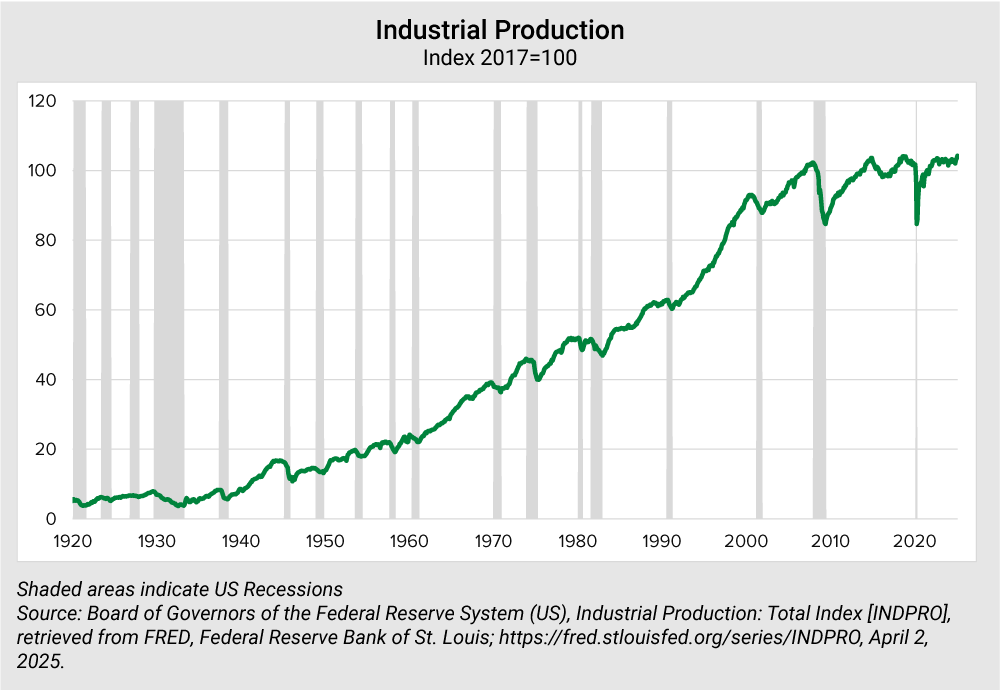

The embrace of globalism has created tremendous wealth around the world and has drastically changed the makeup of the US economy. According to Colin Grabow of The Cato Institute, just 45 years ago, 22% of non-farm workers were employed in manufacturing. Today, that number has fallen to 8%. And yet US manufacturing output has continued to grow through technological advances and productivity gains. Even adjusting for inflation, American manufacturing output is near its all-time high.

Agriculture is another example. In 1800, 75% of workers were employed in agriculture. Today it is less than 2%. And yet somehow we are not starving! Agricultural output has boomed with the help of technology, fertilizer, and productivity. According to the USDA, between 1948 and 2015, farm output almost tripled. We certainly aren’t calling for those farm jobs to come back.

Perhaps Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University said it best:

A principal source of confusion is the difference between jobs and output. Yes, the number of workers in manufacturing has declined dramatically—from around 19 million in 1980 to about 13 million today. But that didn’t happen because America stopped making things. It happened because we got incredibly good at making things.

Productivity in manufacturing has surged thanks to automation, technology, and global supply chains. Just as we now produce more food than ever with just over 1 percent of Americans working in agriculture (down from around 75 percent in 1800), we produce more manufactured goods with far fewer workers. That’s not economic decline; it’s progress.

Also fueling the perception of decline are regional factors. Shuttered factories in Detroit or Youngstown, Ohio, bring concentrated pain and struggle for affected workers. No one denies this. But manufacturing didn’t disappear; it relocated and upgraded. High-tech manufacturing has boomed in other parts of America, creating jobs in aerospace, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and advanced machinery and services. These jobs command much higher wages than manufacturing jobs used to. Output of computer and electronics products has grown 1,200 percent since 1994. Motor vehicle output is up well over 60 percent. America and its workers excel in these industries, where we have significant comparative advantages.

The biggest job and output losses were in sectors like apparel, textiles, and furniture. Apparel and leather goods output, for example, have fallen more than 60 percent since 2007. Should we do something about this?

If we could reverse these trends, it would mean pushing relatively prosperous manufacturing workers back into lower-paying jobs making clothing and shoes. If we could generate a manufacturing boom, we still wouldn’t turn back into a nation of factory workers, because the way to manufacturing competitiveness is through automation.

Then there’s the reality that young people would rather work in the service industry. That leads us to another myth: that a service-heavy economy is somehow weak or unproductive. In truth, services now make up about 79 percent of U.S. gross domestic product. That’s what rich economies look like. As we grow wealthier, our demand for services such as health care, education, and entertainment rises relative to demand for manufactured goods.

— Veronique de Rugy, “No, the U.S. Industrial Base Is Not Collapsing,” Reason magazine, March 2025

Trump’s plan prioritizes domestic policy control over market-driven efficiency, a move that upends the “invisible hand” described by economist Adam Smith in 1776 and about which I often write in these pages. Smith’s invisible hand posits that self-interested choices—like a factory owner chasing profit—naturally allocate resources best, without meddling by government or other policy makers. Trump’s very visible hand of tariffs and incentives instead steers the economy away from a global marketplace and toward national self-sufficiency, a radical pivot from the US’s postwar playbook.

This departure stands out because government control of industrial policy has rarely been the norm in the United States, unlike in places like the former USSR or currently in China, where state planners dictate steel output or technology goals. Since Bretton Woods, the US has largely pursued free trade and a laissez-faire approach, letting markets—not Washington—allocate resources. There have certainly been exceptions—Cold War defense spending or, more recently, the CHIPS Act—but these were targeted, not sweeping. Generally, the US has avoided the unintended consequences of having political parties—Republicans today and Democrats tomorrow—picking economic winners and losers. It’s not just about tweaking trade deals, many of which are demonstrably unfair to the US and deserving of modification; it’s a fundamental change, betting that government can outsmart the market in picking champions—like steel, autos or semi-conductors—over the comparative advantage consensus.

Early Wins

The US economy is the world’s biggest importer, soaking up 14% of global exports. Our trading partners don’t want to lose access to our market. US trade policies matter and these moves by the Trump administration will bring significant changes. Indeed, they already have. Numerous large companies, domestic and foreign, including Apple, Honda Motors, Taiwan Semiconductor, Stellantis, Hyundai, Clarios, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, GE Aerospace, and Meta, have announced intentions to make major investments in manufacturing in the US. These companies alone have signaled cumulative investments of more than $700 billion. In addition, some of our trading partners including India, Vietnam, Israel, and Mexico have made concessions to the US in advance of Trump’s new tariffs. Now that “Liberation Day” has created some certainty about the amount and timing of tariffs, we expect ongoing negotiations to result in an ongoing flood of headlines about new agreements, deals and concessions.

Challenges

While a big market, the US isn’t the only game in town and our trading partners won’t roll over easily. China, the EU and Canada have already retaliated with increased tariffs of their own. Additionally, China, Japan and South Korea are exploring a separate trade partnership to the exclusion of the US. Again, we expect ongoing announcements going forward.

Another major challenge is that global supply chains are complex and tangled. As we learned during the global pandemic, our just-in-time economy, with its efficient processes, lean inventory and globe-spanning transportation system, can be quite fragile. These policies will cause significant disruption and expensive administrative burdens.

The cost of tariffs will be absorbed by producers and/or consumers. Depending on the specific product, more or less of the tariff surcharge is passed through to consumers. For example, for products like clothing, where consumers have the choice to substitute a different product, a producer will try to absorb the cost of the tariff to maintain the customer. For products where there are few substitutes, like an iPhone, producers are able to pass the cost on to the consumer. Because someone absorbs the higher cost, tariffs are often described as a tax. According to US trade representative Peter Navarro on Fox News this week, “Tariffs are going to raise about $600 billion a year, about $6 trillion over a 10-year period.” When federal government revenues increase by $600 billion, that money is obviously coming from consumers or businesses in the private economy. Higher costs equal inflation. If the tariffs stand, we expect higher inflation figures for the rest of this year.

A Bumpy Road Ahead

As we roll further into 2025, we expect the volatility of the last six weeks to continue. As we’ve discussed on numerous occasions, the stock market doesn’t like uncertainty and we’ll be in a fog for some time as a result of the administration’s plans. In the coming quarters, we’ll see how committed Trump and his team are. Will they stick it out if it looks like the US is sliding toward a recession, just before the mid-term elections? Will they hold firm if stocks enter a bear market? They might. With one term to serve, Trump is already a lame duck and he has acknowledged that there will be some pain. His team knows the plan they’ve thrown on the table is an audacious plan, a risky plan. They surely recognize that you can’t undo decades of globalization in a few years. So what are they expecting? Trillions of dollars of new investment in America and a manufacturing boom? That sounds great; you and I can agree that it would be fantastic if we could reduce our dependence on imports, create millions of high-paying jobs right here at home, re-train our workforce, grow our economy at a faster rate, pay down our debt, watch the stock market soar and enjoy national security. But wow! How realistic is that?

We’ll suggest that in the short term, it’s not realistic. A bear market, a recession, a mid-term election, an unforeseen crisis … all manner of things could and likely will prove disruptive to a well-made plan. As heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson is famous for saying, “Everyone’s got a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” But I think we can also agree that the world has changed. China didn’t embrace freedom and democracy as a result of our generous trade policies. Many of our traditional allies are struggling mightily. We find ourselves burdened with an unsustainable fiscal situation as a country, and on our current path, we won’t be able to keep our commitments to our fellow citizens or our foreign allies. The current administration is shaking things up with a risky plan that heretofore would have been rejected by the free-traders on the right but embraced by the left. Yes, things have changed. The market is reacting badly to much of this, and we may end up in the ditch for a time. On the brighter side, more of us are paying attention. We remain confident that we’ll see great progress in our future.

One final note: Headlines will soon be filled with Q1 earnings announcements, and they’ll look solid—a near-term anchor during this policy storm. Our favorite source for earnings forecasts, Yardeni Research, expects the final numbers to show that S&P 500 Q1 earnings grew more than 11% year over year. This would be the seventh straight quarter of positive earnings growth, and the second straight quarter of double-digit earnings growth. I hope this serves as a reminder that the headlines can change, and the news can be positive. And while we’re talking earnings, recall that earnings drive stock prices in the long term. Rest assured that amid all this tariff talk, the people running the companies in which we are invested are paying attention. They are making their way through the fog. They are focused on solving problems, overcoming roadblocks and ultimately making a profit.

In the weeks ahead, we’ll likely be offered lower prices for the shares of the companies we own. That is never a good feeling, but we don’t think we should decide that is a reason to sell. It may take time, but we think our shares will be worth more in the future.

Thank you for reading today … it’s a long one! I hope this was helpful. We appreciate your trust in Bragg Financial and hope the arrival of spring brings you joy.

This information is believed to be accurate at the time of publication but should not be used as specific investment or tax advice as opinions and legislation are subject to change. You should always consult your tax professional or other advisors before acting on the ideas presented here.

1st Quarter 2025: Market and Economy

March 31, 2025Investment Ingredients: Combining Assets for Optimal Returns

May 1, 2025New World Order?

March Madness took on a whole new meaning for me last month. Rather than logging endless hours watching basketball, studying tournament brackets, and, of course, lamenting the fact that my Demon Deacons didn’t get invited to the Big Dance, I spent most of my time trying to figure out the true objectives of the Trump administration with regard to tariffs and trade policy. Count me among those investors who assumed that Trump’s tough talk about tariffs and trade sanctions was just that—tough talk. Up until mid-February, when the stock market hit an all-time high, it was clear that most investors assumed the same.

That changed today, “Liberation Day,” so designated by President Trump when speaking to reporters in the Rose Garden this afternoon. He stated, “April 2, 2025, will forever be remembered as the day American industry was reborn, the day America’s destiny was reclaimed, and the day that we began to make America wealthy again.” He also called it “one of the most important days in American history,” emphasizing its significance as a “declaration of economic independence.” Trump argued that his reciprocal tariff plan—imposing a 10% baseline tariff on all imports and higher rates like 34% on China and 20% on the EU—would reverse decades of unfair trade practices, generate “trillions and trillions of dollars” to cut taxes and reduce national debt, and usher in a “Golden Age of America” by boosting domestic production and jobs. We expect global stock markets to have a very unfavorable reaction to this new plan.

As we enter the second quarter of 2025, it is now clear that the Trump administration is committed to an economic framework that signals a significant shift in how the United States positions itself globally. This vision, a “New World Order” in economic terms, centers on reshaping trade policies and revitalizing American manufacturing. It’s an overwhelmingly ambitious plan that would redefine decades of global trade norms and bolster domestic industry. In this letter, I’ll dig into the thinking of the people on Trump’s team, discuss our trade policy in an historical context, explain why Trump’s plan is such a dramatic departure from the status quo on trade, outline the economic risks of the plan, and finally, discuss implications for investors.

The Core Vision

The administration’s approach, laid out in the “America First Trade Policy” memorandum signed by President Trump on January 20, 2025, calls for a comprehensive review of US trade relationships and industrial capabilities. This isn’t a minor tweak—it’s a reimagining of America’s role in the global marketplace. The goals are straightforward: cut reliance on foreign supply chains, boost national security through economic self-sufficiency, and put American workers and businesses first. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has pushed this hard, saying, “We’re tearing up the old playbook—trade has to work for America first, not the other way around.” Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick calls it a historic pivot: “This is our chance to reset the global board and bring back what we’ve lost; it’s not just policy, it’s a new era.” It’s a break from the free-trade consensus of the last 80 years, and leans on tariffs and incentives to bring economic activity home.

At its core, this plan tackles trade imbalances, the loss of manufacturing jobs, and vulnerabilities like those exposed by COVID-19. It’s a reaction to decades of offshoring and a bet that the US can reclaim its industrial edge. The scope is huge, covering trade deals, tariffs, taxes, and massive industrial investment.

Trade Policy: The Engine of Change

Trade policy drives this agenda. On February 1, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order slapping tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico, and China—25% on most products, with a 10% rate on Canadian energy to ease price shocks. Using the justification of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the Trump administration aims to pressure partners on issues like immigration and drug trafficking while nudging production stateside. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced NAFTA, appears to be in jeopardy as these tariffs challenge its framework ahead of a 2026 review—a big shift in our historical alliances with Canada and Mexico, our two largest trading partners.

The 2025 Trade Policy Agenda, delivered to Congress on March 2, pushed for a “rebalancing” of trade, targeting deficits and practices like foreign subsidies and value-added taxes. It proposed a universal 10–20% tariff on all imports, with a 60% rate being considered for China. It included threats of 100% tariffs on BRICS nations who are considering adopting alternative currencies to the dollar, showing that trade can double as a geopolitical weapon. It announced that steel and aluminum tariffs from Trump’s first term were under review, while export controls were being tightened to guard America’s technology lead and intellectual property, especially from China.

Finally, and perhaps fittingly, I’m writing this letter on April 2, deemed “Liberation Day” for US trade policy by Trump. Today the president announced a 10% across-the-board tariff on all imports and additional tariffs on any country with whom we have a goods trade deficit (we import more goods from them than they import from us). The larger the deficit as a percentage of the amount that country exports to us, the larger the tariff. For example, with China, the US had a trade deficit of approximately $295 billion in 2024 (their exports to us exceeded our exports to them by $295 billion), and their total exports to us were $440 billion. Dividing $295 billion by $440 billion yields roughly 67%, which when halved, rounds to the 34% tariff Trump plans to charge. The net effect of this approach is to punish any trading partner where an imbalance exists. If we buy more from you than you buy from us, we are going to hit you with a tariff. This approach obviously ignores consumer preferences and distorts the free market. Trump’s team says it doesn’t matter, and that the tariffs will immediately create a powerful incentive for our trading partners to buy more from us.

Bringing Manufacturing Back: A Herculean Task

The vision of the Trump administration is that the US would return to being a “manufacturing powerhouse” with tariffs making foreign goods pricier and encouraging US production. The plan calls for cutting regulations, streamlining permitting processes, and providing tax incentives to encourage businesses to invest in US-based manufacturing facilities. Companies, domestic and foreign, are being incentivized to create American jobs and to build manufacturing plants within the United States. Biden-era moves like the CHIPS Act are building blocks, now refocused with an “America First” lens. Finally, recognizing the existence of a significant skills gap, the administration emphasizes the expansion of vocational training and apprenticeship programs through partnerships with community colleges and trade schools.

A Major Departure

The Trump administration’s plan to remake America as a manufacturing powerhouse represents a major shift in US economic strategy, modifying a decades-long commitment to free trade that began with the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. Anticipating the end of World War II, representatives from 44 nations gathered in New Hampshire and signed a compact establishing a global monetary framework—fixed exchange rates, the IMF, and World Bank—to foster open markets and economic stability, laying the groundwork for a global economy. Globalism, the idea that nations prosper through interconnected trade and investment, took root alongside the principle of comparative advantage, which most economists, from David Ricardo in 1817 to modern thinkers, have embraced. This holds that countries should specialize in what they produce most efficiently— making car parts in Mexico, assembling tech in China, or designing microchips in the U.S for example—and trade freely, maximizing global wealth. It’s why your iPhone’s components crisscross the globe before landing in your hand. Your phone would cost far more if built in the US.

The embrace of globalism has created tremendous wealth around the world and has drastically changed the makeup of the US economy. According to Colin Grabow of The Cato Institute, just 45 years ago, 22% of non-farm workers were employed in manufacturing. Today, that number has fallen to 8%. And yet US manufacturing output has continued to grow through technological advances and productivity gains. Even adjusting for inflation, American manufacturing output is near its all-time high.

Agriculture is another example. In 1800, 75% of workers were employed in agriculture. Today it is less than 2%. And yet somehow we are not starving! Agricultural output has boomed with the help of technology, fertilizer, and productivity. According to the USDA, between 1948 and 2015, farm output almost tripled. We certainly aren’t calling for those farm jobs to come back.

Perhaps Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University said it best:

Trump’s plan prioritizes domestic policy control over market-driven efficiency, a move that upends the “invisible hand” described by economist Adam Smith in 1776 and about which I often write in these pages. Smith’s invisible hand posits that self-interested choices—like a factory owner chasing profit—naturally allocate resources best, without meddling by government or other policy makers. Trump’s very visible hand of tariffs and incentives instead steers the economy away from a global marketplace and toward national self-sufficiency, a radical pivot from the US’s postwar playbook.

This departure stands out because government control of industrial policy has rarely been the norm in the United States, unlike in places like the former USSR or currently in China, where state planners dictate steel output or technology goals. Since Bretton Woods, the US has largely pursued free trade and a laissez-faire approach, letting markets—not Washington—allocate resources. There have certainly been exceptions—Cold War defense spending or, more recently, the CHIPS Act—but these were targeted, not sweeping. Generally, the US has avoided the unintended consequences of having political parties—Republicans today and Democrats tomorrow—picking economic winners and losers. It’s not just about tweaking trade deals, many of which are demonstrably unfair to the US and deserving of modification; it’s a fundamental change, betting that government can outsmart the market in picking champions—like steel, autos or semi-conductors—over the comparative advantage consensus.

Early Wins

The US economy is the world’s biggest importer, soaking up 14% of global exports. Our trading partners don’t want to lose access to our market. US trade policies matter and these moves by the Trump administration will bring significant changes. Indeed, they already have. Numerous large companies, domestic and foreign, including Apple, Honda Motors, Taiwan Semiconductor, Stellantis, Hyundai, Clarios, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, GE Aerospace, and Meta, have announced intentions to make major investments in manufacturing in the US. These companies alone have signaled cumulative investments of more than $700 billion. In addition, some of our trading partners including India, Vietnam, Israel, and Mexico have made concessions to the US in advance of Trump’s new tariffs. Now that “Liberation Day” has created some certainty about the amount and timing of tariffs, we expect ongoing negotiations to result in an ongoing flood of headlines about new agreements, deals and concessions.

Challenges

While a big market, the US isn’t the only game in town and our trading partners won’t roll over easily. China, the EU and Canada have already retaliated with increased tariffs of their own. Additionally, China, Japan and South Korea are exploring a separate trade partnership to the exclusion of the US. Again, we expect ongoing announcements going forward.

Another major challenge is that global supply chains are complex and tangled. As we learned during the global pandemic, our just-in-time economy, with its efficient processes, lean inventory and globe-spanning transportation system, can be quite fragile. These policies will cause significant disruption and expensive administrative burdens.

The cost of tariffs will be absorbed by producers and/or consumers. Depending on the specific product, more or less of the tariff surcharge is passed through to consumers. For example, for products like clothing, where consumers have the choice to substitute a different product, a producer will try to absorb the cost of the tariff to maintain the customer. For products where there are few substitutes, like an iPhone, producers are able to pass the cost on to the consumer. Because someone absorbs the higher cost, tariffs are often described as a tax. According to US trade representative Peter Navarro on Fox News this week, “Tariffs are going to raise about $600 billion a year, about $6 trillion over a 10-year period.” When federal government revenues increase by $600 billion, that money is obviously coming from consumers or businesses in the private economy. Higher costs equal inflation. If the tariffs stand, we expect higher inflation figures for the rest of this year.

A Bumpy Road Ahead

As we roll further into 2025, we expect the volatility of the last six weeks to continue. As we’ve discussed on numerous occasions, the stock market doesn’t like uncertainty and we’ll be in a fog for some time as a result of the administration’s plans. In the coming quarters, we’ll see how committed Trump and his team are. Will they stick it out if it looks like the US is sliding toward a recession, just before the mid-term elections? Will they hold firm if stocks enter a bear market? They might. With one term to serve, Trump is already a lame duck and he has acknowledged that there will be some pain. His team knows the plan they’ve thrown on the table is an audacious plan, a risky plan. They surely recognize that you can’t undo decades of globalization in a few years. So what are they expecting? Trillions of dollars of new investment in America and a manufacturing boom? That sounds great; you and I can agree that it would be fantastic if we could reduce our dependence on imports, create millions of high-paying jobs right here at home, re-train our workforce, grow our economy at a faster rate, pay down our debt, watch the stock market soar and enjoy national security. But wow! How realistic is that?

We’ll suggest that in the short term, it’s not realistic. A bear market, a recession, a mid-term election, an unforeseen crisis … all manner of things could and likely will prove disruptive to a well-made plan. As heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson is famous for saying, “Everyone’s got a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” But I think we can also agree that the world has changed. China didn’t embrace freedom and democracy as a result of our generous trade policies. Many of our traditional allies are struggling mightily. We find ourselves burdened with an unsustainable fiscal situation as a country, and on our current path, we won’t be able to keep our commitments to our fellow citizens or our foreign allies. The current administration is shaking things up with a risky plan that heretofore would have been rejected by the free-traders on the right but embraced by the left. Yes, things have changed. The market is reacting badly to much of this, and we may end up in the ditch for a time. On the brighter side, more of us are paying attention. We remain confident that we’ll see great progress in our future.

One final note: Headlines will soon be filled with Q1 earnings announcements, and they’ll look solid—a near-term anchor during this policy storm. Our favorite source for earnings forecasts, Yardeni Research, expects the final numbers to show that S&P 500 Q1 earnings grew more than 11% year over year. This would be the seventh straight quarter of positive earnings growth, and the second straight quarter of double-digit earnings growth. I hope this serves as a reminder that the headlines can change, and the news can be positive. And while we’re talking earnings, recall that earnings drive stock prices in the long term. Rest assured that amid all this tariff talk, the people running the companies in which we are invested are paying attention. They are making their way through the fog. They are focused on solving problems, overcoming roadblocks and ultimately making a profit.

In the weeks ahead, we’ll likely be offered lower prices for the shares of the companies we own. That is never a good feeling, but we don’t think we should decide that is a reason to sell. It may take time, but we think our shares will be worth more in the future.

Thank you for reading today … it’s a long one! I hope this was helpful. We appreciate your trust in Bragg Financial and hope the arrival of spring brings you joy.

This information is believed to be accurate at the time of publication but should not be used as specific investment or tax advice as opinions and legislation are subject to change. You should always consult your tax professional or other advisors before acting on the ideas presented here.

SEE ALSO:

1st Quarter 2025: Market and Economy, Published by Matthew S. DeVries, CFAMore About...

Trump Accounts: A New Vehicle for Long-Term Savings

Read more

Understanding the One Big Beautiful Bill and Its Tax Changes

Read more

Investment Ingredients: Combining Assets for Optimal Returns

Read more

Harvesting the Loss: When Does It Make Sense?

Read more

Playing Catch-Up: Making Extra Contributions for Retirement

Read more

The Tortoise and the Hare: Why Most Investment Predictions Fall Short

Read more